Monday, March 30, 2009

Voucher Shut Down

It ruled Wednesday that two voucher programs created to serve foster children and disabled students are a direct violation of the Arizona Constiution.

Here's what the constitution says. Article 9 Section 10: No tax shall be laid or appropriation of public money made in aid of any church, or private or sectarian school, or any public service corporation.

The voucher programs are a result of two Arizona statutes passed in the spring of 2006 that allowed public money to go to parents in the form of educational grants, used to subsidize tuition at religious or other private schools.

In February of 2007, a coaliton of educaiton and civic groups filed suit in response to the statutes, according to the Arizona Education Association. The AEA was part of the coalition, as was the Arizona School Boards Association, the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona and the Arizona Federation of Teachers, to name a few.

The coalition members call private school vouchers "a threat to the basic right of every child to attain an excellent public education," on the AEA website.

"Vouchers are not sound education policy," said Panfilo H. Contreras, Executive Director of the Arizona School Boards Association.

"They divert funds from an already strapped system and channel them to private organizations that, unlike public schools, are not required to be accountable for how the money is spent or the level of achievement that results. Vouchers also create inequities for students, particularly those who live in rural areas, where few private schools exist," said Contreras on the AEA website.

Several editorial boards sounded off in response to the ruling. The Tucson Citizen lauded the decision, saying "It's time our legislators sought to strengthen public schools instead of routinely seeking ways to funnel cash to private schools."

Robert Robb of the Arizona Republic also supported the court's decision, even though he supports vouchers. Here's his take:

"In response to the court's decision, Verschoor said: "It is a sad day in Arizona that parents are sent the message that they don't know what is best for their children."

That wasn't the message of the court's decision at all. It had nothing to do about whether vouchers were good or bad public policy. There's not a word in the decision about the merits of vouchers. Instead, the unanimous decision found that vouchers violated the plain language of the state Constitution. And, in this, the justices were quite right."

But, others argue the ruling contradicts court precedent. In a guest opinion to the Arizona Daily Star, Vicki E. Murray said, "Opponents claim that scholarships like Rebecca's aid private schools, not students. They fail to mention that Arizona public schools use public funds to send more than 1,000 students to private schools each year when they cannot provide the programs and services those students need. The real issue for school choice opponents isn't principle. It's power."

"Decades of Arizona Supreme Court precedent supports such educational options for families, and for nearly a century the U.S. Supreme Court has also reaffirmed "the power of parents to control the education of their own." Both courts have consistently rejected the assumption, apparently embraced by school choice opponents, that children are mere creatures of the state," she said in the Star report.

Monday, March 23, 2009

Teacher Training

In 2007, more than 60,000 teachers were certified via alternativte programs that allow them to begin teaching before completing all their certification requirements. That number has surged dramatically since the 1990s.

As of 2008, all 50 states and Washington D.C. have some type of alternate route to teacher certification. And, more than half of all current programs have been established in the last 15 years, according to the National Center for Education Information.

Source: National Center for Education Information

So, given that one-third of the nation's new teachers were certified via non-traditional routes, the Dept. of Education's study was designed to investigate the effectiveness of different teacher training strategies.

After evaluating 2,600 students in 63 schools across 20 districts, the authors reached the following conclusions:

- There was no statistically significant difference in performance between

students of alternatively certified teachers and those of traditionally certified teachers. - There is no evidence from this study that greater levels of teacher training

coursework were associated with the effectiveness of alternatively certified teachers in the

classroom. - There were no statistically significant differences between the alternatively certified and traditionally certifed teachers in this study in their average scores on college entrance exams, the selectivity of the college that awarded their bachelor’s degree, or their

level of educational attainment.

In another report also released last month, the Center for American Progress promoted alternative certification programs, saying "these programs are among the most promising strategies for expanding the pipeline of talented teachers, particularly for subject shortage areas and high-needs schools."

The report by the Washington-based think tank went on to say that, "states frequently do not have policies in place to develop and expand robust alternative certification programs," and offered suggestions on how to implement such policies.

Whether or not Arizona should heed the advice is up for debate. The state legislature will soon consider new alternative certification routes, according to a Mar.22 story in the Arizona Republic.

In it, Arwynn Mattix says that "If outcomes in other states provide an example, allowing alternative certification for teachers will not only result in more teachers in the classrooms, it will also increase the number of teachers with math and science degrees and the percentage of minority teachers." Mattix is the associate director of BASIS School Inc., a non-profit that operates two charter schools in Scottsdale and Tucson.

He is opposed by John Wright, president of the Arizona Education Association, who says, "The challenge for alternative certification plans is that most undermine at least one of three areas of quality teacher development: subject knowledge, knowledge of teaching, and supervised practice. These alternative pathways are often faster because they are incomplete."

Monday, March 16, 2009

Part III: Special Inequality

Some kids just fall behind. Sometimes it's a language problem, sometimes it's an attendance problem and sometimes it really is a developmental problem. But as long as a kid is behind enough to warrant special education testing, does it really matter what the problem is?

Some kids just fall behind. Sometimes it's a language problem, sometimes it's an attendance problem and sometimes it really is a developmental problem. But as long as a kid is behind enough to warrant special education testing, does it really matter what the problem is?The National Education Association says YES. Labeling students as disabled when they truly aren't leads to "unwarranted supports and services...and creates a false impression of the child's intelligence and academic potential," said the 2007 report, Truth in Labeling: Disproportionality in Special Education. Here's why:

- Once students are receiving special education services, the tend to remain in special education classes

- Students are likely to encounter a limited, less rigorous curriculum

- Lower expectations can lead to diminished academic and post-secondary opportunities

- Students in special education programs can have less access to academically able peers

- Disabled students are often stigmatized socially

- Disproportionality can contribute to significant racial separation

Matthew Ladner agrees. As Goldwater Institute's vice president of research, Ladner has authored studies examining the miniority over-representation in special education - two of which were referenced in last week's post. Here are excerpts from an interview last week:

"Special education is not remedial education. Teachers are not doing the kids any favors by mislabeling them. And there are errors on both sides, especially with SLD (Specific Learning Disability). The process for labeling kids SLD is so profoundly unscientific."

"It is not ok to label a kid that doesn't have a disability. It can permanently change what the kid expects of himself, and what the teacher expects."

"The thing that everyone ought to agree to is we need a correct diagnosis. For, if no other reason - and there are plenty of other reasons - it's taking resources away from kids that do have disabilities."

This is the final installment of the Special Inequality series. Look for the full story on Borderbeat.net.

Monday, March 9, 2009

Part II: Special Inequality

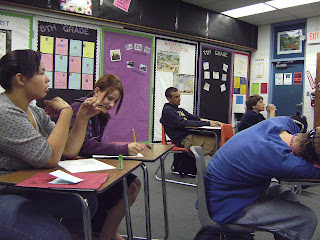

Mrs. Stevenson helps two students in her first period social studies class at Flowing Wells Junior High School on Thursday, March 5, 2009.

Mrs. Stevenson helps two students in her first period social studies class at Flowing Wells Junior High School on Thursday, March 5, 2009.When English is not the native language of special education students, meeting their educational needs gets more complicated, said Tara Stevenson, a special education social studies teacher at Flowing Wells Junior High School.

School psychologists are trained to test students who teachers suspect belong in special education. For students who are not native English speakers, the test is administered in their native language - but, the school psychologist is not necessarily proficient in that language. If they are placed in special education and don't know English very well, the special education accomodations aren't as effective, Stevenson said.

Some would be better served in the English Language Learners program instead, she said, but therein lies the problem. Students can't do both - either they're in special education or the language program - leaving administrators and teachers to decide which program is most beneficial.

Some would be better served in the English Language Learners program instead, she said, but therein lies the problem. Students can't do both - either they're in special education or the language program - leaving administrators and teachers to decide which program is most beneficial.They don't always make the right decision. In the report referenced in last week's post, "Race to the Bottom: Minority Children and Special Education in Arizona Public Schools," Matthew Ladner of the Goldwater Institute wrote of one girl's disatrous special education experience.

Here's an excerpt:

"Magdalena enrolled in a suburban, predominantly white, Phoenix-area district as a kindergartner. A non-native English speaker, Magdalena had not learned to read and write in her native Spanish. Not surprisingly, Magdalena had some difficulty in her early course work.

When Magdalena reached third grade, school district officials approached Magdalena’s mother, Maria —who does not speak English— about enrolling her daughter in a “special program.” District officials explained that Magdalena had a learning disability, and that she would be better

served in this program.

Maria says that school district officials never explained that they believed her daughter had a neurological condition that would impair her from learning. Nor did they explain to her that she had a right, under federal special education law, to have a separate evaluation of her daughter by outside experts at school district expense. The district’s only effort to inform Maria of her rights as a parent was to give her a booklet that was not only written in English, but also written in what Maria described as highly technical language."

The story goes on to talk about how unchallenged Magdalena was once placed in special education, as she was forced to repeat third grade material year after year. She was even given the same AIMS math test, with the same math problems, several years in a row.

When her mother realized how poorly Magdalena was being educated, she attempted to pull her out of special education - and met with resistance. She finally succeeded when Magdalena headed to high school, where she jumped from 3rd grade to 9th grade level coursework.

While it's impossible to "difinitively evaluate," Ladner cites simple racism as one of the main causes of over-representation of minority students in special education. "This possibility—that special education programs are used to segregate minority children—is entirely consistent with findings from previous research."

While it's impossible to "difinitively evaluate," Ladner cites simple racism as one of the main causes of over-representation of minority students in special education. "This possibility—that special education programs are used to segregate minority children—is entirely consistent with findings from previous research."The previous research he refers to is the 2003 Goldwater Institute report, "Race and Disability: Racial Bias in Arizona Special Education," based on data from the Arizona and U.S. education departments.

There were several important findings - but the most personally disturbing one was this: "Even after controlling for school spending, student poverty, community poverty, and other factors, research uncovered a pattern of predominantly White public school districts placing minority students into special education at significantly higher rates. As a result, Arizona taxpayers spend nearly $50 million each year on unnecessary special education programs."

Monday, March 2, 2009

Part I: Special Inequality

The U.S. Dept. of Education's Office of Civil Rights conducted a survey of the nation's special education programs in 2000. The results show Arizona's minority students are disproportionately represented in special education programs.

"Overall, when comparing the combined rates of children with Emotionally Disturbed, Mentally Retarded, and Specific Learning Disability labels, both American Indian and Hispanic males are labeled at a rate 64 percent higher in schools that are 75 percent or more white than in schools that are 25 percent or less white. The same figure for white male students shows an almost 50 percent decline in disability rates. These results come about despite the fact that minority students attending predominantly white schools are less likely on average to grow up in poverty than minority students attending predominantly minority schools."

The above excerpt summarizing the Office of Civil Rights' data comes from the 2004 Goldwater Institute report, "Race to the Bottom: Minority Children and Special Education in Arizona Public Schools."

The study cites several causes for the over-enrollment of students in special education:

- Perverse financial incentives

- Avoidance of standardized testing

- Misuse of special education as a remedial education

- Segragationist impulses

- Changing the state's special education funding formula

- Instituting universal screening for the identification process

- Creating a parental choice program for children with disabilities

The problem of minority over-representation in special education is an old one, and remains a key indicator of inequity in the nation's educational system - a sadly ironic fact as special education was born of the civil rights movement.