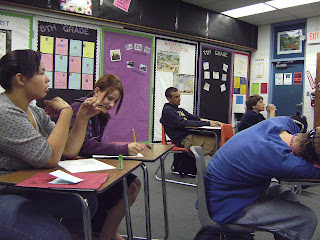

Mrs. Stevenson helps two students in her first period social studies class at Flowing Wells Junior High School on Thursday, March 5, 2009.

Mrs. Stevenson helps two students in her first period social studies class at Flowing Wells Junior High School on Thursday, March 5, 2009.When English is not the native language of special education students, meeting their educational needs gets more complicated, said Tara Stevenson, a special education social studies teacher at Flowing Wells Junior High School.

School psychologists are trained to test students who teachers suspect belong in special education. For students who are not native English speakers, the test is administered in their native language - but, the school psychologist is not necessarily proficient in that language. If they are placed in special education and don't know English very well, the special education accomodations aren't as effective, Stevenson said.

Some would be better served in the English Language Learners program instead, she said, but therein lies the problem. Students can't do both - either they're in special education or the language program - leaving administrators and teachers to decide which program is most beneficial.

Some would be better served in the English Language Learners program instead, she said, but therein lies the problem. Students can't do both - either they're in special education or the language program - leaving administrators and teachers to decide which program is most beneficial.They don't always make the right decision. In the report referenced in last week's post, "Race to the Bottom: Minority Children and Special Education in Arizona Public Schools," Matthew Ladner of the Goldwater Institute wrote of one girl's disatrous special education experience.

Here's an excerpt:

"Magdalena enrolled in a suburban, predominantly white, Phoenix-area district as a kindergartner. A non-native English speaker, Magdalena had not learned to read and write in her native Spanish. Not surprisingly, Magdalena had some difficulty in her early course work.

When Magdalena reached third grade, school district officials approached Magdalena’s mother, Maria —who does not speak English— about enrolling her daughter in a “special program.” District officials explained that Magdalena had a learning disability, and that she would be better

served in this program.

Maria says that school district officials never explained that they believed her daughter had a neurological condition that would impair her from learning. Nor did they explain to her that she had a right, under federal special education law, to have a separate evaluation of her daughter by outside experts at school district expense. The district’s only effort to inform Maria of her rights as a parent was to give her a booklet that was not only written in English, but also written in what Maria described as highly technical language."

The story goes on to talk about how unchallenged Magdalena was once placed in special education, as she was forced to repeat third grade material year after year. She was even given the same AIMS math test, with the same math problems, several years in a row.

When her mother realized how poorly Magdalena was being educated, she attempted to pull her out of special education - and met with resistance. She finally succeeded when Magdalena headed to high school, where she jumped from 3rd grade to 9th grade level coursework.

While it's impossible to "difinitively evaluate," Ladner cites simple racism as one of the main causes of over-representation of minority students in special education. "This possibility—that special education programs are used to segregate minority children—is entirely consistent with findings from previous research."

While it's impossible to "difinitively evaluate," Ladner cites simple racism as one of the main causes of over-representation of minority students in special education. "This possibility—that special education programs are used to segregate minority children—is entirely consistent with findings from previous research."The previous research he refers to is the 2003 Goldwater Institute report, "Race and Disability: Racial Bias in Arizona Special Education," based on data from the Arizona and U.S. education departments.

There were several important findings - but the most personally disturbing one was this: "Even after controlling for school spending, student poverty, community poverty, and other factors, research uncovered a pattern of predominantly White public school districts placing minority students into special education at significantly higher rates. As a result, Arizona taxpayers spend nearly $50 million each year on unnecessary special education programs."

No comments:

Post a Comment